|

Click here for a downloadable and printable PDF of this dissertation.

|

Murdoch University |

|

An Other Voice From Aceh |

|

|

|

|

|

By Owen Beck |

|

|

This thesis is presented as part of the requirement for the

Degree of Bachelor of Media with Honours at

Murdoch University 2007

A hard copy of this thesis, complete with videos, picture galleries and appendices is available at the Murdoch University Library.

|

|

Copyright Acknowledgement

I acknowledge that a copy of this thesis will be held at the Murdoch University Library.

I understand that, under the provisions of s51.2 of the Copyright Act 1968, all or part of this thesis may be copied without infringement of copyright where such a reproduction is for the purposes of study and research.

This statement does not signal any transfer of copyright away from the author.

Full Name of Degree: Bachelor of Media with Honours

Thesis Title: An Other Voice From Aceh

I declare that this thesis is my own account of my own research and has not been presented for assessment at any other university

Owen Beck

Date 7th February 2008

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank my supervisor, Dr. Josko Petkovic, for his perception, insight, and guidance and, at times, perseverance during my Honours program.

I would also like to thank my children, Gracie and Noah, for hanging in there and putting up with an old man who tends to do things other dad’s might never dream of. I love you both dearly.

ABSTRACT

This dissertation consists of two parts:

1. This paper, which documents my journey at a personal, academic and philosophical level.

2. An Other Voice From Aceh, the major production piece produced for this Honours dissertation.

Part 1 – The Report

This paper describes my thoughts and production processes during my Honours program. I am required to submit a journal of my experience in the Honours program at Murdoch University and have incorporated the journal in the process of writing this paper. I have experimented with use of dialogue between my supervisor and me, highlighting various moments and turning points in the process of completing the program. Using theories developed by a number of thinkers, mainly in the field of psychoanalysis, I attempt to describe illuminating moments, concepts and ideas as these theories are applied to my own responses to trauma as well as the representation of those responses through film. Just as any good story has a number of traumas or challenges and attempts to overcome, my Honours journey has been a road of rewarding perseverance.

Part 2 – The Production: An Other Voice From Aceh

The original edit of An Other Voice From Aceh was produced prior to much theoretical thought or application, but with passion, determination and in adventurous spirit, and is deconstructed post event; analysed from something of a psychoanalytical perspective. Chris Garratt might consider this something of a postmodern approach, “working without rules in order to find out the rules of what you’ve done”. (Garratt, 2001, p. 50)

The final edit of An Other Voice From Aceh provides clues for an uninformed audience to help them unlock some of the secrets of the original text. It could be considered a consolidation of some of my previous filmic efforts while simultaneously pointing to a future of further examination and contemplation, action and films to come. This version introduces, more overtly, links with theories of Sigmund Freud, Jacques Lacan and Bruno Bettelheim. It is an expression of things I have found very difficult to express in words; an externalisation of my own trauma and the journey to recovery.

CONTENTS

Part 2 – The Production: An Other Voice From Aceh.

REFLECTING ON LACAN - The Mirror Phase (or Stage)

SESSION 4: HIROSHIMA MON AMOUR

SETTING THE SCENE – Beginning in Papua New Guinea

TELLING STORIES WITH BRUNO BETTLEHEIM

1001 ARABIAN NIGHTS – THE FRAMING STORY

Appendix 1 The Personal Journey

Appendix 2 Rick's Café Américain

Appendix 4 Touching on Altruism

Appendix 5 Cambodia, Trauma, Photos, Film and Mirrors

Appendix 6 Should I Be Reading Jung?

PREFACE

In the following pages you will find an edited and stylized version of some of my interaction with my supervisor during my Honours program. The final extracts were selected and written in cooperation, collaboration and agreement with my supervisor.

SESSION 1: DREADLOCKS

O: Hey Josko.

J: Hi Owen! It is good to see you again. Do come in. (Jocular) Just let me get my scissors while you sit down and we can then cut the dreadlocks from this dog-tail beard of yours!

O: No! I need to keep it for the time being.

J: It is good to have you back in the program again.

O: It is good to be here again. It has been a while.

J: More than 10 years! It only seems like yesterday. You did some impressive work then. I still recall it vividly: Buyers of Benetton. Terminal Sorrow …The pregnant women dancing. How can one forget!

How are the children – Gracie, Noah? Noah must be 11 like Misha?

O: They are really good. Gracie’s an amazing actor and Noah’s my travel buddy. I see them regularly. There were some problems for a while … And with you? How is Misha?

J: Misha is great. He lives in Canberra with his mum now but I get to see him every holidays…

And you; you have been teaching for a while now. Do you still retain your links with technology?

O: No not really.

J: I thought we had lost you to technology for a while. You had the Casablanca market cornered - it seemed. We called you Mr Casablanca and we were going to give you an honorary degree of some sort for some generous endowment from you. We could have called it the Casablanca Endowment. I thought it would be a most fitting title for a film school endowment…. But then you disappeared.

O: Yeah. That is all pretty much over.

J: Do you still keep in touch with your old partner Rob? He seems to be very busy these days from what I hear.

O: I see him now and then, but I have been pretty much out of circulation. Life’s been pretty weird, Josko.

J: Well now that we’ve got you back let us find some worthwhile project for you to work on. Your knowledge of technology and computers is most fortuitous as computer generated effects and IT are all the rage. So let us find you some spectacular IT challenge and get you going on your program. What do you say?

O: Josko, I think I am over that stage of my life if I ever was really in it. My engagement with technology was really just a means to an end. I’m actually interested in doing something closer to human beings and human values.

J: I am happy to hear that and share your sentiments. I usually start off with students by reminding them of prevailing fashions and intrinsic strengths… or perceived strength it seems in this case. What kind of human interest story did you have in mind?

O: I don’t know exactly but I think I want to explore something to do with Muslims. We’ve demonised them so much, especially Indonesians, but I often find them to be people of real joy and happiness. It is certainly not what I see in our own culture.

J: This is indeed an interesting topic. The newspapers are full of it. I cannot believe what we are doing in Iraq. But how and where exactly are you hoping to anchor your search for a story?

O: Well, I was hoping to do something in South-East Asia; Indonesia, Sumatra. Perhaps I could go there to make a film.

J: What a great place. As you know I took a group of students to Indonesia in 1991. What story would you like to work on?

O: I am not sure yet. I was hoping to find an angle by talking about it with you. Something I could write about in academic terms.

J: Do you speak Bahasa?

O: No, I don’t. Not at all. I think I just want to connect with ordinary people and language may not be such a great problem.

J: Is there someone you are going to team up with?

O: I have some friends up there but I wasn’t really planning to team up with them.

J: Is there a topic you wish to pursue or someone authoritative on the topic of your choice? Ideally someone that is living in the area you wish to investigate.

O: Not specifically. It is a broad kind of interest. It could be about their family lifestyle and culture.

J: Have you been reading about their history and culture?

O: Not really, I find that these things don’t matter all that much in personal interactions.

J: What can I say to this? What topic should we look for here? His journey seems like a simple displacement to another time and another place. Displacing what? Something, or some problem? Forgetting about it or taking it somewhere where the problem is unrecognizable? What problem? We need to find out the dynamo of this displacement if this story is to move.

J: OK Owen, it seems to

me that the best thing to do is for you to jot down a number of topics that may

be of interest to you and then we can talk again. Write as much as you wish

but I would recommend that you begin with one script idea you wish to do here

in the culture that you know well. We need to identify your thematic interest

in depth and we can best do that with the circumstances you know best. We can

then see how the Indonesia topic and Islam fits in.

J. The Islamic family script seems like an antidote to all that has happened to him. This may not be surprising following the breakdown of his relationship. He speaks softly but one wonders if there is anger behind this. If so, how can we deal with it in a script?

If this is the cause behind his journey to Sumatra where does this displacement lead him? Forward or backward in time: Forward to confront the problem he has encountered and to find a solution for it? Or backward in time and in this way avoid the confrontation with the problem if the problem is insurmountable? If this is so I should look for a displacement backward in time towards some safe place, to the careless nostalgia of the childhood Imaginary to start with.

This again brings me to my tried and true thesis for artists and creative writers. But the theory will have to be given piecemeal and at the right time. Next time?

SESSION 2: CASABLANCA

THE PARK

O: Life was very difficult for me post-marriage. Suicide was not an option because I had to be here for my children, whom I dearly loved. I found myself considering the appeal of life on the streets. The idea presented the temptation to retreat to a no-paperwork, no-responsibility community of like-minded people who had surrendered a certain kind of struggle. It was strangely enticing, but once again, this would not help my children.

In 2003 I, and my kids, began having lunch on a weekly basis with people who inhabit the streets of North Perth. It was here that I escaped the pain of ‘real life’. Our weekly gathering grew into quite a community and created a sense of personal reconciliation with some Indigenous Australians as well as a building of friendship with Middle-Eastern Muslim refugees. I have enjoyed the company of many different people and shared many stories of struggle and mateship.

These barbecues became the most peaceful and relaxing part of my week for quite some time. By engaging in an open, sincere, caring manner, with people I should culturally be at odds with, a situation has been created where I could confidently walk through Hyde Park at any time of day or night and someone would come to my rescue if I were to come into any kind of trouble. I may not have been able to reconcile with my ex-wife, but at least I had reconciled with someone, and besides, I felt safe and appreciated.

J: Owen, I read the writing you sent me and we should now try to find a focus in it that we could develop further. We can develop the homeless and refugees story. What do we want to say about them? Or rather what would you like to say about them? There is a slightly religious tone when you speak of these situations in which case it could be something with a Salvation Army appeal.

O: Let me try and explain. I want to communicate how important my family was to me and how lost I felt when my family disintegrated. I was desperate. I needed something to replace the human bonds that family gave me previously. This is what I found in the park. I used to go there and talk to these people that no one wanted to talk to, only to find out how interesting they were. It is not to say that they were simply interesting or simply good. They had their good days and bad days like the rest of us. But it was interesting to discover that it was just that! Good days and bad days. Like anyone else. Sure, in some cases their bad days had to do with excesses of drinks, or drugs, or petty theft. But soon these judgments disappeared as I got to know them and they got to know me.

These people became family. I was interested in their problems and they were

interested in my problems as I might be with someone in my own family. My

kids embraced them too and often it would be Noah or Gracie who, at the ages of

7 and 12, would approach a mob sitting under a tree and ask if they wanted to

join us for lunch.

J: (jocular) Is that when you started putting dreadlocks in your beard? Keeping up with the local fashions?

OK let us think about this. There are two ways of

approaching this. Either we focus on your story or on their story. It seems

to me at the moment that your script concept has more to do with your needs and

your search for a family. This would be a more authentic way of approaching

your script concept in the first instance, rather than think about Sumatra or

homeless friends. Maybe we should explore this further over a coffee.

J. Over a coffee he told me his story again. She was his soul-mate, his song-mate. I recall that she had a past of her own. We worked together on this in Blossom. I had assumed that they were both saved; that they had saved one another, but it must have all unraveled. It seems this unraveling had to do with more dramatic stories that led back to her childhood; more trauma and complications. It was the usual stuff, enough to put her off men. But it seems that he was the one left alone in the wash. There was now another woman with her, he said. He felt diminished in the eyes of his children, he said. For a while, Gracie pushed him away. He felt hurt and powerless. But slowly this too is now getting resolved. Noah was always by his side.

Is this what his homeless people story is all about?

He seems direct and spontaneous. Is anything hidden here? So, why the journey and displacement? Why Sumatra?

J: Owen, when is the first time you went to the tropics? In reality or in your imagination?

O: The first time I went to the tropics is when I was born. My father was a teacher on an island off the south coast of New Guinea and the whole family lived there. These were happy times.

J: So this story does go backward, as I hypothesised. Backward towards ground zero, toward the childhood Imaginary to start with. Is this his core melody? His song? Is this where the resolution to his script problems lie – in the enchantment of images that speak outside words, music rhythm, rhyme enchantment, intoxication soothing the pain that is in his life?

J: This is an interesting story. Can you make sure you write it down and send it to me before we meet again?

J: How useful is this move backward to the point where memory stops and dissolves? I am approaching his Imaginary nostalgia as something that illuminates his problem but in my thesis this is the “solution” that all of us embrace. We all need our daily opium of images.

DID I

MENTION ACEH?

O: You know, I’ve been working on a film I shot during my last trip to Indonesia. It was after the Boxing Day tsunami hit Aceh. Can I show it to you?

J His words came unexpectedly and as a complete surprise. It was like a turning point in a script when everything that has happened until then stops and has to be considered anew. It left me unguarded and incredulous except to note that it was his second connection to the SE Asia.

J: Of course I would like to see it. What were you doing in Aceh?

O: I went there to help. A friend from Indonesia called me on my mobile after the tsunami. I still remember the moment. I was standing alone in a shopping centre during the festive season, surrounded by happy shoppers and holiday-makers. I wondered what I was even doing there when I received a call from my Indonesian friend, Tutut. She told me about some orphans in a town called Meulaboh and asked me if there was anything I could do. That question messed with me. Of course there was something I could do – I live in the wealthy West. I couldn’t answer ‘no’ with any kind of authenticity or integrity. I would get there, or I would die trying. Of course, according to the Australian media representation of Acehnese people, I probably should have died trying! (cynical laughs). I bought tickets which took me to Jakarta and then made my way to Aceh. I got there without speaking a word of Bahasa.

In many ways it was an exercise in vulnerability, since I didn’t speak their language and they didn’t speak mine. I was completely at their mercy and they looked after me at every step along the way, showing me great hospitality and care.

I’m going to use this film to raise awareness of some of the needs in Meulaboh and to raise money for bikes to help some kids get to school.

J. He showed me his short 15 minute film. It starts with a Digital Globe image of Banda Aceh before the Boxing Day devastation which is then dissolved quickly over the image of Banda Aceh after the devastation. The images then slowly move into close-ups of bloated human flotsam as the Jingle Bell song washes over all of these gruesome images of death. The contrast was crushing and unbearably poignant, almost obscene – death and destruction of lives, families and communities accompanied by the Jingle Bells tune – an anthem of family happiness. Whose family? His or theirs? Both? It does not take much analysis to work out the dynamo of this cathartic combination that compelled him to travel to Sumatra.

If he carried a family catastrophe within him then here in Aceh he could see a family catastrophe staring him in the face like a mirror. Here was a visible manifestation of everything he had until then endured taken to its devastating limit. The symmetry of internal and external anguish must have been in place already on Boxing Day when he could see the biggest catastrophe that the human family has endured in our living memory splashed on screens all around him accompanied by the sounds of Christmas. All that was needed for this inside and outside anguish to fuse together was a single call he received in the shopping centre. He may not have recognized at that time that these images of grief could also be an expression of his own life, but I have no doubt that he must have felt it. Sharing grief is visceral. You don’t have to think about it. You just feel it and it is this feeling that moves us to tears. These feelings are evident in his production; in the small inconsistencies and slippage which draw one’s attention. The early images of death and devastation were followed by prolonged images of a journey across Indonesia. These travelling shots from a vehicle were accompanied by an ambiguous solo tune creating almost a musical video clip effect: His characteristic musical signature. The words were undecipherable but following the earlier images of death this musical interlude had a slightly jarring feeling as if the journey itself was becoming a story. And yet, this journey was his journey and this Aceh story was his story.

I wondered if other viewers would recognize clearly, if they did not know any of his personal details, his voice which was all too clear to me. By all accounts he found it difficult to deal with the unhappiness in his own life and this external catastrophe was tangible. Something could be done about it. He rushed to help. Action. Nothing was going to stop him. He observed the people in Aceh overcome their grief. Compassion. He observed their life begin anew. Hope. He observed the children play and laugh again. Healing. He made a film after many years of grief. Renewal. He then returned here to resume his studies. Creativity.

He said he wanted to give the people of Aceh a voice and had made an effort to silence his own. I said his was the only voice I could hear and that the film mirrored his own journey. I asked him to write as much as he could about the journey he had been on and the production process to date.

J: Owen we now also need to start framing your scriptwriting with some theoretical reading. I would like you to start reading about Jacques Lacan. He is considered by most as writing in psychoanalytic traditions. This is not to suggest that this tradition is a correct one or the only one worth pursuing, but Lacan does give us an interesting toolbox by which to approach images and the way we relate to image. In the first instances Lacan tells us that images in the exteriority are connected to who we are. He would say that in certain circumstances we are the image.

I would like you to read about the early stages of development he describes as the Order of the Imaginary. He may give us an angle of how to deal with your Sumatra Journey which in your case may also be your New Guinea journey.

O: He spoke in fairly abstract concepts about some of the theoretical aspects that I should start to consider. He also did numerous sketches. It all made some sense at the time, but I’m not sure I really understood what he was saying.

O: Lacan says “the words [we] use mean more than [we] mean in using them” (Leader, D. Groves, J., 2005, p. 59), and I think this was very evident from time to time. I misunderstood him and he misunderstood me. These misunderstandings were familiar territory though, and I had confidence that we would eventually come to a point of mutual understanding.

Besides suggesting I read Lacan, he mentioned something about my vulnerability in Aceh being not unlike a rebirth, in that I was not only dependent on those around me but was even without language to a large extent. He also suggested I watch a TV program that was showing soon, on altruism, because it was about people who went to the tsunami affected areas to help. He was right about rebirth; there was a profound sense of a new life being kick-started, and I came across the idea of rebirth in a number of my readings later in the program. The Kindness of Strangers (Skirving, 2006) was also interesting and I spent a few weeks looking into altruist theory. It was really helpful at a personal level, but perhaps a little tangential.

O I started reading Lacan. Meanwhile, during December and January, with my son, Noah, I once again headed for Aceh, this time equipped with my laptop and a backpack loaded with books. Noah and I delivered about 270 bikes to kids in Meulaboh on Boxing Day 2006 – the second anniversary of the tsunami, the mother of all traumas – in my lifetime at least. This brought a sense of personal closure for me. This had been a deeply satisfying adventure.

We then took time in Lake Toba where I was able to focus on my reading. From there we moved on to Cambodia, where I shot a documentary for an organization that works with vulnerable women and kids. Finally, we settled into a seaside town called Kampong Saom. Noah swam and played with street kids while I drank coconut juice and read Lacan.

I found the reading really hard going, having to read it over and over, taking copious amounts of notes. It had been over a decade since I had even heard of Lacan and it was slow sinking in. The friendly people and beautiful places helped ease my re-entry to the world of academia.

SESSION 3: LETTER TO EROS

REFLECTING

ON LACAN - The Mirror Phase (or Stage)

In Christian theology, man is made in the image of God. The Latin translation for the word ‘image’ is imago, which has acquired a number of other powerful connotations over time. Carl Jung suggests that “the individual forms a personality by identifying with imagos that emerge from the collective unconscious, a shared reservoir of mythical figures and scenarios” (Zuern, Imago, 1998). Foucault might say we’re more of a social construct of institutions and disciplines. Lacan’s mirror phase refers to a “particular case of the function of the imago, which is to establish a relation between the organism and its reality – or, as they say, between the Innenwelt and the Umwelt” (Lacan, 1977, p. 4).

According to Lacan, the mirror phase happens somewhere between six and eighteen months of age; at a time when a child is uncoordinated, vulnerable and insufficient. When the infant, who is in pieces, sees a seemingly coherent and complete image of itself, or of an other it identifies with: “a transformation… takes place in the subject [as] he assumes [the] image” (Lacan, 1977, p. 2). This identification could be seen as an example of captation; “a process in which an object in the external world (most frequently another person) so ‘captivates’ the subject that it becomes a component in that subject’s self-image” (Zuern, 1998).

The mirror phase is a time of empowerment; as the infant sees others doing things, they realize they can also do those things. My own mother recounts the story of my brother’s first steps. As soon as he saw his twin sister stand up and walk, he did also. The mirror phase is also a time of alienation, as the world around us dictates who we become and we distance ourselves from the real. It could also be useful in understanding empathy and vicarious trauma, since “if I am in the place of another child, when he’s struck, I will cry. If he wants something, I’ll want it too” (Leader, 2005, p. 22).

This identification with an other happens in what Lacan calls the imaginary register, “emphasizing the importance of the visual” (Leader, D. Groves, J., 2005, p. 22). To see Lacan’s infant as analogous with the cinema spectator is reasonably straight forward, and when Lacan’s Ecrits was published, in 1966, the mirror phase became “widely adopted by theorists in order to explain the psychological experience of film spectators who ‘lose’ themselves in narrative film” (Kronberger, 2000, p. 21). Josko Petkovic draws on Lacan’s Imaginary Order when he suggests this relationship is like:

A child in an Imaginary relationship with the world [existing] neither here nor there but as a conflation of both – as a synthesis of here and there. One could describe this Imaginary symbiosis (in which the child has limited control) as possession of a kind. Perhaps one could even say that the child is in a trance (Petkovic, 1994, p. 15).

O: When I went to see Lord of the Rings: the Two Towers (Jackson, 2002) the cinema was jam packed. I found myself sitting front row centre. Here awaited my portal to another world; as the big screen engulfed me I was completely lost; as were my real-world problems, traumas, challenges, forms to fill in, schedules, relationships. Here, the “dissolving of the distinction between here and there, audience/screen, actuality/fiction” was most complete (Petkovic, 1994). Three hours later, I was spat back into the real world, but the experience of another existence came with me. I felt revived. Since then, I have often chosen the front row, simply for the all-consuming experience, the escape, that cinema offers

O: We identify with characters in films in a ‘mirror phase kind of way’ all the time. Characters like Travis in Paris Texas (Wenders W. , 1984), Karol in Three Colours White (Kieślowski, 1994), and Parry in The Fisher King (Gilliam, 1991) come to mind. As I look back, I realize they all lost their wives – in very different ways – and also experienced a real sense of rebirth and renewal.

I came back to Perth feeling like I was beginning to understand a portion of Lacan. I had found him very challenging in many ways but had connected aspects of my own journey with the mirror phase. The mirror phase seemed to explain my identification with various on-screen characters as well as the tsunami victims I had seen on television.

J. Owen, until now we have used Lacan to tell us how images outside ourselves tell us something about what we feel inside. We have talked about how this informs our viewing of cinema and how we identify with those we see on the screen. We should also note that Lacan attributed this type of mirror development to the early stages of childhood and that subsequently we abandon this way of relating with the world and use words instead. We think in words, we plan with words, we love and aspire in words, we define ourselves in words as rich or poor, beautiful or ugly, man or woman etc. But the sense of Imaginary unity remains dormant within us nevertheless and according to me is it is evidently present within artists and visual artists in particular.

O Yeah right. So the imaginary is much closer to the real. You know, I’ve often thought of art as the communication of things impossible to articulate in words and what you’re saying reminds me of Nietzsche when he says that “music is distinguished from all the other arts by the fact that it is not a copy of the phenomenon… but a direct copy of the will itself” (Gane L. &., 2005, p. 15) I reckon he might have added film to this in some cases, if film had been around in his day, since music is the juxtaposition and combination of sounds in both a temporal and non-temporal sense, so film is the juxtaposition and combination of both sound and image in both the temporal and non-temporal. The tension and release that exists when these combinations and juxtapositions are applied artfully communicates so much more than words. Anyway, that’s probably an aside.

J Well, I have spent much time developing the thesis that this Imaginary realm is also enticing to those who encounter difficulties in the world of words which is the primary world that most adults reside in. If we abandon words then the Imaginary realm unfolds for us and in the first instance this realm will lead us backward towards the intense imagery of the childhood. This movement back in time need not stop here with the Imaginary realm. According to an obscure and controversial theory of Freud each individual’s consciousness has a pathway that leads us backward in time to non-existence. He called this pathway drive Thanatos – the death instinct. The mechanism that he used to explains all this is trauma. Trauma always encapsulates a memory of what existed before we encountered trauma and it is this return to time before trauma that defines the backward move for Freud. In your story it is possible to see a whole series of traumas. These are in fact your most intense memories.

So let us do some time travelling. Can you write something about these memories that encapsulate your primary traumas. Can you also find out all about the Nirvana Principle that is Freud’s Death Instinct, Thanatos.

SESSION 4: HIROSHIMA MON AMOUR

SETTING THE SCENE – Beginning in Papua New Guinea

O: I was born on a small, tropical Island called Daru, off the south coast of Papua New Guinea, in 1964. I don’t remember it, as we moved to Port Moresby when I was very young. I do, however, remember much of my seven years in Port Moresby as a paradise of tropical weather, mangoes, pawpaws and bananas, playing in the rain, swimming in warm water, catching fish, exploring the neighbourhood and living a life free of worry. Somewhat adventurous, I was oblivious to what the rest of my family was doing, but I knew I was dearly loved and cared for and I never felt unsafe. One day, I hope to take a runabout from far north Queensland to revisit Daru and retrace my mother’s walk from the house to the hospital to give birth.

Since coming to Australia in 1972, I have always wanted to return to Papua New Guinea, but have not had the opportunity. As a twelve year old boy, I saw film footage of the surf and village at Lugundri Bay, Nias – a mysterious island off the coast of Sumatra in Indonesia. Something inside of me jumped; here was a place that I could play in the rain again, and enjoy the fruit and freedom of tropical, coastal life. I haven’t been there, yet.

As a teenager and in my early twenties I pursued an idealistic life of music, surf and travel. Designing wetsuits facilitated travel to great waves in Victoria and California. I think I pretty much always cared, and as part of the surf culture I would pick up grommets (young surfers) who had left home at a young age to live by the sea and give them a good feed once a week. Playing music opened up further opportunities to travel and to have something of a voice concerning what I saw in the world around me. During my BA years at Murdoch University, I found a place of empowerment in video production, being able to produce music videos as further expression of my frustration and questioning of the world around me.

Buyers of Benetton was my first real video production, questioning the racist, exploitative, capitalist ideologies dominant in my world.

O: In 1990 I married, and in 1991 we had our first beautiful baby – a girl we named Gracie Holliday. In 1996 we had Noah Jimmy and began to raise a fairytale family. Then somewhere along the line my world ended. It was as if all atomic bombs went off at once and destroyed the entire world.

There’s no point trying to describe it in words. I can only circle around it, describe it by degrees, by comparison.

I will try.

Eleven years ago, on a morning like any other, a close friend of mine took to his family with a screw-driver and hammer. He hurt them. Alarm was raised and when he heard police sirens, he jumped into his car and led them on a high-speed chase. The chase took them from Geelong to the Great Ocean Road, where he pulled over beside the ocean and drank a bottle of battery acid. He died, roadside, at one of his favourite surf spots, clutching a photo of him and his wife on their wedding day. I was his best man.

Ten years ago, a close friend came down with a Leukemia that pretty much no-one survives. I went to Melbourne to say goodbye and shortly after I left the doctors gave him an hour or two to live. He didn’t die. Today he tours the world playing music, on a walking stick, with bags for his bowels and bladder, and about 30% vision remaining after the damage the cancer has done.

Around the same time, my sister was also diagnosed with advanced Melanoma. She died nine months later, after an incredibly painful and somehow hopeless fight. As I arrived on my bicycle for my morning visit, my mother ran out crying, “come and say goodbye to your sister”. I kissed her goodbye and she died.

Six years ago, my wife drove down the driveway to be with her lesbian lover. This was ten times more painful than kissing my sister goodbye. I loved my wife dearly and had persevered eleven years hoping certain things would blow over; they didn’t blow over, they blew away. My children were devastated, and I tried to rebuild a new life for them. I took on teaching so I could be with them in holidays, moved house and did all I could to care for them. This was literally the end of my world as I loved it – to nearly quote Michael Stype of REM fame (Stype, 1987).

Three and a half years ago, my father had strange stomach pains. He soon died from Pancreatic Cancer after an agonizing struggle. I had struck up a relationship with a woman at this time and was deeply infatuated with her. She had recently gone to Tasmania to study and couldn’t take me ‘needing’ her at the time of my dad’s death, so hung up on me during a long-distance telephone call the day he died, never to speak with me again.

Three years ago, I was diagnosed Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and tried various therapies which helped or didn’t help in varying degrees.

INTRODUCING THANATOS

In a phrase, Thanatos, otherwise known as the Death drive, is a drive to return to a previous state. Its name can be somewhat misleading, in that it conjures images of destruction, aggression and suicide. Thanatos does include aggressive impulses, but these are generally associated with self-preservation, so may in fact be considered conservative by nature. The theory, being based on the idea that we have a drive or desire to return to a previous state, when taken to its logical conclusion, means reverting to a state of non-life, or death – hence the name ‘Death Drive’.

Opposite to Thanatos is Eros, the drive for life and pleasure, which through sex results in the perpetuation of our species. While Eros would seek adventure and excitement, the conservative Thanatos may err on the side of safety and retreat, hence contributing to the survival of our species though self-protection.

Thanatos has been discounted as un-Darwinian - misunderstood as a drive towards death, which would eliminate a species. Freud’s Thanatos, however, is based in evolution. He suggests that the human baby encapsulates the entirety of its evolution. Just as humans have evolved from a single-cell over billions of years, the nine months from conception to birth is a retelling of that story (Sulloway, 1979, pp. 393 - 412). Genetically it’s reasonable to say that my make-up is that of my parents, combined, who were a result of their parents, and so on. My existence is testimony to the events and struggles, traumas and recoveries, threats and survivals of a genetic line that dates back millennia and beyond.

According to Freud, “only by the concurrent or mutually opposing action of the two primal instincts – Eros and the death-instinct –, never by one or the other alone, can we explain the rich multiplicity of the phenomena of life” (Freud, 1937, p. 243). On the one hand, I crave adventure; on the other, I yearn for the safety of what once was. In a state of post-trauma, I desire to go back. Back to my marriage and the nuclear family I once had. Back to PNG, Daru, or the carefree tropics. Back to a place of freedom, peace, safety, nurture. Back to my childhood.

O: In 2005, I decided to go to Bali. Government travel warnings were at a maximum but being post-suicidal you really don’t care too much about that stuff. The plane was all but empty – as were the streets of Bali devoid of Australians. Ironically, during this first trip, the subway bombs went off in London. The moment I stepped off the plane I felt like I had arrived home. I spent time surfing, hanging out with locals, eating great food and drinking cheap beer.

During my time in Bali I became friendly with a disenchanted Muslim journalist named Tutut. Her biggest hero in life was Mother Theresa, who inspired her to join a humanitarian Non Government Organisation (NGO) working in Meulaboh, Aceh. As soon as I returned to Perth, I bought another plane ticket.

SESSION 5: SCHEHERAZADE

J. Owen, I want you to read Bruno Bettleheim. He gives us an interesting angle on approaching narratives – all narratives. He describes the superficial and manifest level of the story – in your case it could be your journey to Sumatra and your homeless friends. He then also indicates how this surface story is only a resolution of some more interesting and latent problems. In your case we could possibly relate this to the breakdown of your family life or some element of it – if we wanted to do this in the script. The deeper level is the dynamo and the core of the story. Bettleheim also gives a procedure by which one comes to deal with the core story and to that extent come to terms with the problem that it encapsulates. The framing story Scheherazade is particularly illuminating.

TELLING STORIES WITH BRUNO BETTLEHEIM

Bruno Bettelheim suggests that fairytales help us deal with various challenges in life by representing our unconscious issues in their storyline and characters and offering solutions to those problems. He elaborates on how Cinderella helps us deal with sibling rivalry, Fairy Godmothers and Wicked Witches help us cope with the fact that our mothers have positive and negative sides, and Jack and the Beanstalk is about becoming independent.

Through the process of transference, “the displacement of one’s unresolved conflicts, dependencies, and aggressions onto a substitute object” (Felluga, 2006) we are able to externalize our subliminal conflicts and struggles, and resolution for our fairytale, or on-screen, protagonist becomes metaphoric or symbolic resolution of our own issues. Susan Lien Whigham suggests that “individuals who suffer from [Post Traumatic Stress Disorder] often communicate using metaphors…” and that “we can help individuals recover from trauma by learning to communicate with them using metaphorical language” (Whigham, 2006). So it seems that listening to stories or watching films could help us deal with deep, subconscious problems and challenges, including healing from damage caused by the greatest of traumas. Bettelheim suggests “we must somehow distance ourselves from the content of our unconscious and see it as something external to ourselves, to gain any sort of mastery over it” (Bettelheim, 1991, p. 55). As we return time and time again to revisit the trauma in yet another film, each time the ‘anxiety level’ is reduced a little.

1001 ARABIAN NIGHTS – THE FRAMING STORY

In short, the King of Samarkand had caught his wife in bed with one of his slaves. After having her executed, in a state of trauma and grief, he went to visit his brother, the King of Bukhara. While there, he discovered his brother’s wives were all having sex with his slaves. As much as this gave the king of Samarkand some sense of consolation (his situation was somewhat less tragic that his brother’s) this all lead to a great mistrust of all women. The king of Samarkand decided to sleep with a different virgin every night and then have her killed the following morning, since they were not to be trusted.

When all but two virgins, Scheherazade and her younger sister, had been killed, it was time for Scheherazade to be with the King. Before they were to sleep together, Scheherazade asked the King if she could see her younger sister one last time, as she knew her own destiny. The King allowed it, and Scheherazade, in front of the King, began telling her sister an enthralling story. She didn’t finish the story and the King decided he needed to hear the ending, so he allowed Scheherazade to live one more day. The next night, Scheherazade finished the story and began another. She was allowed to live one more day. This continued, and after three years (1001 nights) of hearing the stories the King had not only fallen in love, but was healed of his anger at woman.

This story begins with great trauma; discovering his wife had cheated on him. The King’s journey takes him to a place of real despair, and he becomes bitter, cynical and filled with hatred. However, in great wisdom, through her storytelling;

Scheherazade draws ever narrower circles around the trauma her husband has

suffered, first with variations on the theme, and then feeling her way closer

and closer to the fiery core of his misery, that which drove him to “craziness

and insanity”… he awoke, cured from his intoxication, and said: ‘By God, this

story is my story, and this tale is my tale; I was full of rage and fury until

you guided me back to rightfulness!’ And he once more took command of his

reason, cleansed his heart and came to his senses. (Ammann,

2006)

This wonderful example of the healing power of storytelling is somewhat replicated in how a child will cling to a certain story, wanting to hear it over and over. Bettelheim suggests that, as a certain fairy tale strikes a chord with where a child is at developmentally, emotionally, or in regards to challenges they may be facing, they need it repeated many times in order to really take on the healing, hope or guidance contained in the story. Once the particular story has done its job, and the child has mastered the issues they were faced with, they move on to other stories (Bettelheim, 1991, p. 58).

In developing theory on Thanatos, Freud considered trauma and the tendency of trauma victims to repeat or reenact unpleasant experiences. They displayed such “neurotic symptoms as involving fixations to, and compulsive repetitions of, traumatic events” (Sulloway, 1979, p. 396). This return to traumatic events is about reducing, by degrees, the anxiety that such traumatic events produce – a zero response being the ultimate goal. Regarding film, it could be suggested that we all have had traumas in our lives and by repeatedly visiting trauma through film, we gain consolation and reduce the impact of real-life trauma.

Thanatos, repetition and externalization now complement the mirror phase in illuminating my journey and production. By externalizing, or projecting, my own trauma onto the victims of the tsunami, I then went and did something to help. In doing so, I was bringing healing to my own trauma – metaphorically. I was also, once again revisiting trauma; this time one much bigger than my own, which helped reduce my own level of anxiety about my personal trauma.

SESSION 6: PERSONA

O: There is now a sense of theory incorporated in my journey and my film, but the challenge remains to make it accessible to an uninformed audience. At this stage I have completed one version of the film, which I have used to raise money and awareness and it stands as it is, but there are so many other issues that I now need to bring to an audience’s attention.

J Owen, have you seen Persona?

O Yes, a couple of times, but not recently.

J Watch it again. You’ll find it relevant to where you’re at with your own film. Pay close attention to the opening sequence. Also have a look at Helen Kronberger’s Honours thesis on Bergman?

O OK. Actually I helped Helen out with editing snippets of Persona for her thesis. It’ll be good to read her paper.

Kronberger’s paper on Bergma’s Persona had a strong focus on Lacan’s mirror phase. It was useful in reinforcing my understanding of its relevance to film theory. What I found really useful in terms of further developing my film, though, was Bergman’s opening sequence (Bergman, 1966).

New ideas were starting to fall into place so I had a clearer idea of where I could take the film now. I wasn’t sure quite how the experimental stuff would tie with the documentary as such, but set about working on it. I did a number of cuts, with varying use of the Jingle Bell Rock and audio samples referencing other films to help create a sense of narrative and trauma in particular. I also worked with a number of images and sequences, some from my previous films and others of folks in the park, to highlight the theoretical underpinnings of the production as well as the personal journey.

Archival footage – my history. Immersion in water – (re)birth. Countdown from 9 – the film apparatus, foetal development. In reverse – Thanatos. Audio heartbeat reversed – ultrasound. Picture Start – (re)conception.

Here, in a state of death, a phone-call triggers re-conception and rebirth. A new life of images and music. A new journey begins in a tropical paradise with very few spoken words.

With the opening sequence pointing to theory and setting the scene for the rest of the film, I finally completed An Other Voice from Aceh, two years after receiving a call for help.

WRAPPING IT UP

My time in the Honours Program could be seen as somewhat cathartic. I saw my own trauma outside of myself when the images of the tsunami were splashed on the television screen. I could do something about this external trauma, so set about to solve my own problem – delivering bicycles to children in Meulaboh. This saw a return to study and a rebirth of creative expression through film, which led to opportunities in Cambodia to contribute to the lives of more trauma victims through creative works. As was King of Samarkand, I have been surrounded by stories of trauma, which are my own story.

As I type these final sentences, I glance across to the newspaper rack in a small café on the river front in Phnom Penh. The headline is Understanding Trauma in Cambodia. It’s a good read. I hope to move here long term in the next year or so; I’ve become comfortable amongst so many other real-life trauma stories. The newspaper article states an irony; that trauma victims can “find that their losses have produced valuable gains” (Witzel, 2007). I hope to make films here and to train locals, in order to empower.

According to Nietzsche “All writing is useless that does not contain a stimulus to activity” (Gane L. &., 2005, p. 10). I wouldn’t say film that doesn’t stimulate to activity is entirely useless, as comical relief, for example, has a valid function of its own, but I am most interested in moving people to action. I have a strong desire to communicate at the deepest level, and, for me to further understand the human psyche and our experience with cinema – how we interact with it – will empower me in my future film-making exploits to achieve that goal of profoundly deep communication which results in change. I plan to produce a film that somehow projects a complex image of the human psyche in all its contradictions, struggles, conflicts and traumas, onto the screen. I will need to immerse myself in both theory and the real world in order to really know at an intellectual and subconscious level how that will take place.

I need to continue being creative.

BLUEBEARD

Dear Josko,

I have been doing some finishing touches on my dissertation and will email you something in the next day or two.

You may remember me telling you about a fourteen year-old Cambodian street kid being the only person to ever recognize the symbolic relationship between my marriage break-down and my beard length? Well, You will be pleased to know that I have shaved my beard after not trimming it for six years. I have saved the dreadlocks and will frame them. I am pleased that the reason for shaving was for woman.

This afternoon I’m going to start shooting a short film for an organization that’s working with vulnerable young people. I’ll interview a couple of women who are supporting their family who live at the rubbish tip. The film will be used to inspire people to help. I promise I’ll get the dissertation finished!

Cheers,

O

Appendices

The following appendices are a collection of elaborations on a number of activities, processes, distractions and theoretical observations that occurred during my Honours program. I have drawn from them in the process of writing my main paper.

Appendix

1

The Personal Journey

I had received a call from Tutut, a friend I had met on a trip to Bali. She had been to visit some orphans in Meulaboh, Aceh, after the Boxing Day Tsunami. She had asked me if there was anything I could do. Of course there was!

I bought my ticket to Jakarta, and over the next weeks I shared with others what I had decided to do. Some people seemed a little perplexed and others seemed somehow inspired; either way they were all supportive and some gave me stuff and money to buy things for the refugees in Meulaboh. By the time I left I had established contact with a guy in Jakarta called Doni Wijaya. He offered to pick me up at the airport in Jakarta and take me to the wholesalers to buy art supplies and sporting goods. My faith in humankind was being somehow renewed.

I had decided to journal my trip with video. Having been somewhat angry at the west, I would show my audience how I went from Perth to Aceh, how I engaged with strangers, how they treated me, how safe or unsafe is it, how Muslims don’t all want to kill us, how little it cost, how we can go, give, contribute to the world around us. I was cynical about travel warnings and apparent manufacturing of the fear of the ‘other’ and wanted to test that cynicism. If they were right, I may not come back home, but if I was right, I would be able to confidently tell others to ignore travel warnings and enjoy their neighbouring countries.

The Indonesian

Quest

Our plane descended into Jakarta late on the night

of April 11, 2006. As the City came in view it struck me that if a bomb goes

off there tomorrow, it wouldn’t hit me. In fact, if one went off every day this

week it would be very unlikely to hit me. Jakarta is a city of 10 000 000 by

night and 12 000 000 by day, so the odds are very much in my favour.

I stepped into the humidity and felt like I had arrived home. I credit the fact that I was born on a small island off the couth coast of Papua New Guinea, with the sense of familiarity arriving in Indonesia. Various people tried to sell me taxi rides, but Doni was going to pick me up. I sat in a big airport in a huge city full of people the Australian media tells me to be scared of and felt completely safe - even with a fairly huge language barrier. Doni arrived and we crammed my stuff into his small car before heading through several toll booths and eventually arriving at a humble guest house. I stayed here, in air-conditioned, hot-showered, western-toileted luxury for a couple of nights for about $26AUD all up.

Doni was good to me. He spent an entire day taking me around Jakarta and we bought 1200 packets of crayons, pencils, rulers and other educational supplies, as well as a bunch of soccer balls and volley balls. He’s an amazing man. It turns out he runs a small, ‘grass-roots’ NGO (non-government organisation - humanitarian) and is incredible when it comes to logistics.

After a couple of days in Jakarta, I sat next to a young Muslim woman called Feta on the plane to Medan, Sumatera. In broken English, she introduced me to her mother and we tried to talk about life in Medan. Upon arriving in Medan, I took my cues from the crowd, following them into a small bus, then getting out when they got out, and entering an airport building with them to collect my luggage. There were many people yelling, probably about taxi fares, and as I waited, Feta came and offered me a lift. With Feta, her mum, brother and boyfriend, we squeezed into a small car and they took me to the place I had arranged to meet a woman called Frefty. I was delighted to be meeting Muslim people who didn’t want to kill me, didn’t want to conquer the world, and in fact offered me wonderful, warm hospitality.

Frefty was a friend of Tutut’s, and had offered to meet with me in Medan while I waited for the bus to Meulaboh. She had also organised my bus tickets and another friend of hers offered to show me around Medan - a busy city with the most anarchic road rules I have come across. We visited the Sultan’s palace and found a place to eat, then headed back to the pick-up spot and I waited for the bus.

The bus trip was unbelievable! 14 hours of incredible road racing in an eight seater. It’s about 300km as the crow flies, but probably a few times that once you factor in the multitude of hair-pin bends inching their way down one mountain and up the next. The roads were in pretty poor shape, by Australian standards, and there were plenty of times we needed to slow down to a crawl. I think this trip is done at night because it’s safer, in that the driver can see the lights of oncoming vehicles ahead of time. I was in one of two small, cigarette-smoke-filled, identical minibuses in convoy, listening to Indonesian ‘doof’ music that was extremely repetitive, had lots of echo on all vocals, but somehow grew on you after fourteen hours of winding roads journeying through the night. It really was frantic, with the right indicator flashing the whole time so oncoming traffic could judge how close to shave their pass. We clipped my rear-vision mirror as we passed a truck and the driver didn’t flinch – we just kept on driving.

As we descended the Acehnese mountains the sky behind us had become pale in pre-emption of the sun’s arrival, and a very full moon was setting in a clear sky over a still, still ocean – still, except for perfect surf wrapping around the various headlands to settle on quiet beaches lined with the roughly built (by Australian standards) homes and shops that made up yet another small Acehnese fishing village. I had fantasised about places this beautiful since I was a kid and I fondly remembered the old-school surf imagery of the 1970s with their coconut palm-lined paradise beaches. Yet this was also a harsh environment; torrential rain, dense humidity, small villages barricaded on one side by steep mountains and thick jungle, and on the other by a huge ocean that randomly throws a few nasty surprises. It struck me that the natural environment the Acehnese people live with was much like a marriage – so challenging, yet so beautiful.

Already I had begun to shape some kind of profile of the people there, without ever meeting them; I was about to meet people of incredible character. They say ‘perseverance produces character, character hope’, and I was about to find hope and inspiration in what many in the West would consider a dangerous place, where it seems fundamentalist Islam has dominated for years, and which is under strict, Sharia law; where civil war has ravaged and natural disasters have devastated.

We arrived in Meulaboh around 9am. Evidence of NGO presence was plentiful, with new, small, cubby-like houses lining sections of the road, piles of rubble along the verge as building supplies, timber fishing-boat factories by the riverside, Oxfam water tanks, UNICEF school bags, hard-working people with big beautiful smiles.

I was dropped off at the office where Tutut worked and we talked about how to distribute the goods I had purchased in Jakarta. Things had become complex; her boss was upset that I had come to Meulaboh and was intending to be nice. We argued the point, that from my perspective, being nice is how we are supposed to live life, and to him, being nice is work, so required special government paperwork. It was a shame really, and I became a little disillusioned.

Tutut took me for a tour of the damage the Boxing Day Tsunami had done to this delightful fishing town. The sun was setting over a still and seemingly friendly ocean, as people gathered at the seaside where there were once houses and shops and now is rubble. There was quite a bit of tropical regrowth after a year and a bit, and it was hard to believe they now fish, in boats, on a lake that was high-density housing so recently. I was stunned by the devastation, yet moved by the seemingly high spirits of the people. I couldn’t help but wonder how we might have dealt with such a catastrophe here, in Perth.

After the tour, I took a becak (motorcycle with sidecar) to the hotel where I was going to stay and as I hopped out, I heard the voice of Raja “Hello Sir”. I turned to meet a wonderful eleven year old boy who wanted to be my ‘guru’ and teach me some Bahasa Indonesia and a little Acehnese in exchange for me teaching him some English. I had no real plans at this stage, so I was delighted to have someone to hang out with. We talked in broken snippets of mostly English, along with a fair bit of body language and charades. I had an Aussie-rules football in the hotel room so I went in and got it, pumped it up and played a bit of kick to kick with Raja and a bunch of his mates. They were a great lot of happy, friendly, respectful, and hospitable young people.

I spent some time with Raja most days while I was there and ate in the small warung his parents owned next to my hotel. Before I left Meulaboh, I interviewed him. It brings tears to my eyes even now, as I recall his story of what happened the day of the Tsunami and how he lost his five friends, two brothers and a sister. I have come to care deeply about this incredibly courageous child with his positive attitude that inspires life after death.

I had met a guy called Mr Freddy. He was working with an NGO, and had a real heart for the people. He offered to take me to visit a refugee camp and find ways of sensibly distributing the art supplies and sporting goods I had purchased in Jakarta. We met with the leader of a camp of about a thousand, in makeshift houses made out of tarpaulins and a little timber. I asked him if there was anything I could do to help, as a non-NGO tourist who intends to return in December. He told me they needed bikes for the kids to ride to school. There are 270 school-age kids in this camp and the bikes cost about $50AUD each. I explained something about Christmas, and that it was a time of giving in Australia, so I would ask people in Australia to buy a bike for a kid in his camp. He was delighted, and said he would make sure every kid writes to the person who buys them a bike. I was deeply moved with by this idea of ‘reconciliation’ between the Islamic East and the Christian West.

I had the opportunity to interview another one of the leaders in the camp. This was yet another tragic story; as he was stranded in Meulaboh for ten days before he could go back to Banda Aceh, where his family was. He finally managed to go back home to find his whole family, wife and three children, all dead.

I have shed many tears for the people of Meulaboh. I returned home to Australia and made a short film which I used to raise awareness and money for the bikes. I also returned to Murdoch, gaining illumination of my journey through application of theory and completed An Other Voice From Aceh in such a way that the theoretical application is now accessible to a broader audience.

I returned to Meulaboh with my ten year old son, Noah, to deliver 270 bikes on Boxing Day 2006 - exactly two years after the tsunami. This completed a deeply satisfying adventure.

Appendix

2

Rick's Café Américain

In the film Casablanca (Curtiz, 1942), having been hurt more by love than by war, a somewhat cynical Rick Blaine (Humphrey Bogart) established a café that became a community of people from different and often oppositional, political, ideological and cultural backgrounds.

I was married for nearly eleven years. In 2001 it finally all came crashing down and I was left with an empty house filled with what had become strange memories. I dearly loved what I had and philosophically I valued it a great deal. I was now one of those failures who hadn’t given his family enough time because he needed to work to get the money to buy the stuff we just have to acquire in order for those we love to be happy. I was the guy who must have done something to make her walk away, who would re-train and change jobs so he could be with his kids more often, who wept an ocean of tears as he watched his kids endure an enormous upheaval - begging their parents to work it out.

When you are desperate you do desperate things – or at least you think about it. I have always been a bit of an adrenaline junky, so I thought about exciting ways of suiciding but I couldn’t do it. I dearly love my kids and no matter how much I wanted it all to stop, I had to persevere. I needed community. I put some things in place and struggled on trying to develop new relationships. I called on old mates and hung out with them from time to time, but often felt like I didn’t fit any more.

With post-marital financial problems, the anger and manipulation that goes on in family courts, the venom that was spit around when we were trying to sort our arrangements, I found the idea of homelessness a pretty appealing escape. Once again, this wouldn’t help my kids, so once again I would persevere. But surviving wasn’t just for my kids’ sake; somehow, I believed that perseverance would build character, character hope, and hope may sustain me.

Being in a time of real need myself and having considered the appeal of homelessness, I found myself empathising with those in need and decided that it might be a good thing to engage with those living in the parks of Perth. I could perhaps offer them something small - friendship and food -and they would become my new community where I would feel a sense of belonging, if not family. In 2003 my kids and I went to an inner-city park with a small barbecue we bought from the Quokka and asked some of the people there if they’d like to share lunch with us. Our first new friends were Iraqi refugees; a couple with two kids. He is now a journalist, but would sometimes talk about life in Iraq and driving a tank in the first war against ‘George Senior’. These beautiful people were once ‘the enemy’, and are now our dear friends. I wasn’t sure what to do with this but it was definitely politically challenging and motivating. I was growing; at a certain level, through circumstances I would wish upon no-one.

When the barbecues began we were doing it in a park near a main road. Most days people would go past and hurl racist slurs at us. I started to get glimpses of the Aboriginal perspective in particular. It was deeply impressed upon me that these people were treated badly on a daily basis, yet they are still open to friendship with white folks like me. In stark contrast, as I have discussed issued of racism with my high school students, it has became clear that we often generalise fear of Aboriginal people after just one negative encounter, or rumour of a negative encounter, with Aboriginal folks.

During these times I have come across a common thread in the stories of homeless men of European descent. Not all of them, but many took to the street in response to some kind of trauma, often family or relational breakdown or the loss of a loved one. It reminds me of Parry in The Fisher King (Gilliam, 1991); after his wife was shot dead he moved to live on the streets. It seems that the idea of ‘quitting’ is a reasonable option and is chosen by many who have been through similar scenarios to me – some suicide; others relocate - sometimes travelling great distance, other times moving to the street.

As these new friendships developed, I became more acutely aware of the racism towards the Aboriginal and Middle Eastern people in our community. With the events of September 11, 2001, and the ‘allies’ invasion of Iraq, the anti-Muslim rhetoric heated up. I was particularly disturbed by various letters to the newspapers, which accused, condemned, and generally perpetuated fear and hatred of the ‘other’. I found myself angry at letters written by Jim Dawson of Cloverdale, claiming that Muslims have a “divine mission to conquer the world” like “the Nazi regime and the communists”. I happen to know Jim Dawson of Cloverdale is a professional Christian Missionary and I can’t help wondering whether he is on a divine mission to conquer the world himself. Here, in the West, we had to create and maintain an ‘enemy’ in Islam and nurture hatred for that enemy in order to invade Iraq – rather opposite to the altruistism seen in what I imagine should be Jim's message to the world – love your enemy.

Over a few years, this barbecue idea grew. There were often twenty or thirty people of various cultural backgrounds waiting in the park on a Sunday afternoon to share life over a feed. Others joined me bringing food and it became a great time of community and acceptance; valuing each other’s life experience, sharing the hard times and encouraging each other. I have engaged with those from cultural backgrounds I was previously unfamiliar with and whom the media would often present as an ‘other’ to be feared. My time in the park became my Rick's Café Américain. Much to my delight, I have recently heard that others have picked up the idea and are doing similar things in other parks around Perth.

Appendix

3

The Document (ary)

I had begun this documentary with mixed emotions but deliberate intent. I felt a real connection with the pain and trauma people had been through, and, dissatisfied with my own lack of response to this, was determined to do something to help. I was convinced others were in a similar position, so wanted to document my journey to pave the way for those who may want to become active themselves. Furthermore, I was of the opinion that the media had been feeding us inaccurate information as they monsterised Muslim people and Indonesians in particular. This angered me and I wanted to prove my position. My film would be one that sarcastically tells those in the wealthy west to get off their arses and do something useful to bring about reconciling with those we are at odds with. If you love your enemy, you will soon have no enemy.

With a small HDV handicam equipped with a wide-angle lens, I recorded myself speaking to the camera about how safe I felt in Jakarta and how well I was being looked after. I showed my potential audience around the room at my guest-house and explained how I found it and how cheap it was. I told them which airlines they could fly with if they were to do a trip like this, how much it would cost. I interviewed Indonesians who told us not to listen to our government, and that they would look after us. I recorded significant parts of the journey as well as information that would support my initial intended production ideas.

It seemed there were a number of different ways I could have documented life in post-tsunami Aceh, all of which had been done before. I could have researched thoroughly and taken a small crew to shoot in more of a traditional-style television documentary with well-articulated English voice-over. Or perhaps a current affairs or news-style production would have been another option. As time went by, I became more and more interested in human stories about individual people rather than the spectacle of the event, the amount of money we have donated or the way money may have 'disappeared' on its way to the people who really needed it. Statistics and politics didn't really do it for me either. If I could somehow give voice to one or two individuals who had endured such an enormous upheaval as the Boxing Day tsunami, I would be more than happy. I continued to journal, but stopped talking to camera and instead spent time building relationships with people. I asked some of those new-found-friends if they would like to tell people in Australia their story by speaking to the camera. Sitting in very small warungs (restaurants) and cubby-like houses with people who were rebuilding their lives from scratch, I struggled to hold back the tears as they shared life with me - and ultimately my audience.

In Bali I took a week to begin editing and have some translation done, as I speak no Bahasa Indonesia myself. I edited in the same restaurant each day, where one of the waitresses was happy to translate. Once subtitles were in place, I was in a position to be able to begin editing proper, as I then knew what my friends in Meulaboh had said. I was still a little mixed as to how to construct a film that would communicate all I had intended. I recorded some address to camera, to be used as introductory and voice-over etc. but decided that voice-over wasn't necessary. I would make every effort to remove my voice, for it was a story of suffering, perseverance, hope and humanity that had moved me, so that's what would also move my audience.

At various times in life I have written songs and played music, and have enjoyed making music videos. One of the films that has inspired me is Baraka (Fricke & Magidson, 1992), with its use of music and images and an obvious lack of spoken words, and I decided to experiment with the idea of using small, meaningful moments from interviews with people from Meulaboh, intercut with music and images that would speak of my journey and convictions. This change in direction was to profoundly impact the finished production, as the anger and frustration I set out with had somehow melted. An Other Voice From Aceh started to very much mirror my own experience - not only in my journey to Aceh, but my journey through great upheaval and trauma, and the road to recovery.

A reasonably complete edit was used to raise awareness and money to assist refugees in Meulaboh, but the way the film mirrored my own journey wasn't terribly obvious to the uninformed viewer. My Honours supervisor made some suggestions as to how I might give an audience better access to my journey as well as the psychoanalytic theories that could be used to explain such a journey. This turned out to be quite a challenge, since the film was already working and had deeply moved audiences: I was a little tentative about making major changes.

I had seen a range of films that dealt with similar political issues, others that dealt with similar personal issues and yet again, films that dealt with similar theoretical issues. Violent Blue Light Ghosts (Eames, 2004) seems to be a response to a very dissatisfying western world and the way we deal with the ‘other’. It touches on religious conflict (Muslim v Christian). Similar issues, different approach. I went through the punk thing decades ago, so sympathise, but am more interested in attempting to bring reconciliation at an individual and personal level. Million Dollar Baby (Eastwood, 2004) looks at self-forgiveness, substitution of lost love ones. The Fisher King (Gilliam, 1991) also touches on self-forgiveness, but the Robin Williams Character, Parry, is the one I really relate to. He's lost his wife and moved to the streets as a response. In his own way, he's a protector of other people on the streets. Three Colours White (Kieslowski, 1994) and Paris Texas (Wenders W. , 1984) also follow the journeys of men who have lost their wives. These are wonderful stories of recovery and rebirth. Casablanca's Rick Blaine (Curtiz, 1942) has travelled a great distance to rebuild a life post love-trauma and surrounded himself with an eclectic mix of people - this is getting even closer to my story. Yet again, Elle in Hiroshima Mon Amour (Resnais, 1959) is “Angered by the fundamental inequality imposed by some nations on others; by the fundamental inequality imposed by some races on others; by the fundamental inequality imposed by some classes on others” (Resnais, 1959). She travelled great distance to love the enemy after love has caused her great trauma; greater than the trauma of war. She speaks of having seen news footage of the devastation of Hiroshima. This seems somehow close to my own story and my film - half documentary, half narrative film, it opens with harrowing images of disaster - the annihilation of human beings en-masse. Bergman's Persona (Bergman, 1966) points to theoretical aspects such as the mirror phase, his own previous work, as well as making direct reference to the apparatus of film.

Drawing from stylistic and narrative elements of films like Hiroshima Mon Amour and Bergman's Persona I set about to finish An Other Voice From Aceh in such a way that the thoughtful and reflective viewer would be able to access my story as well as the theoretical underpinnings of the overall narrative. My film now opens with a sequence consisting of snippets from my own previous films. Through the use of audio, it points to the conflict between the celebration of Christmas and the inner turmoil experienced by many - exacerbated by such expectation of celebration and high spirits. It points to the apparatus of film and the blurring of the line between reality and cinema. It points to the trauma of family breakdown and love lost. It also points to Freud's Thanatos, Lacan's Mirror Phase and the idea of rebirth - after a return to a state of non-life, new life is stimulated by a call to adventure. This creates a sense of temporal reflection - two lives existing either side of a state of non-life; the mirror. They are the same, but they are different.

The film has necessarily evolved and I am now satisfied that An Other Voice From Aceh functions on a personal, political and theoretical level.

Appendix

4

Touching on Altruism

My supervisor suggested I watch The Kindness of Strangers (Compass, 2006), screened on an episode of Compass on ABC2 . It looked at a number of people who responded to the tsunami in similar ways to me - going to help in practical ways. Several interviews were done with various 'experts' from various fields in an effort to explore why people behave in such ways; why altruism exists in a species whose evolution depends on self-preservation.

There were a number of conflicting points of view presented, and I drew no real conclusion myself, but it did spawn some interest so I researched altruism and discussed the concepts of altruism and egoism with some of my high-school classes.

I had been inspired by a number of great altruists during my lifetime and I found the idea of 'benefiting' in some way from the things I had done to help others bothered me. It was somehow hypocritical. I had thought along basic lines of a single continuum with egoism at one extreme and altruism at the other. It seemed that any action could be measured to sit somewhere along this continuum and any degree of personal satisfaction had a negative, or egoist, impact on this. I think most people tend to think along these lines and cast judgement accordingly, as have I done most of my life.

Using this continuum, one might measure heroic altruists, such as Gandhi, Martin Luther King and Jesus up one end and Charles Manson down the other.

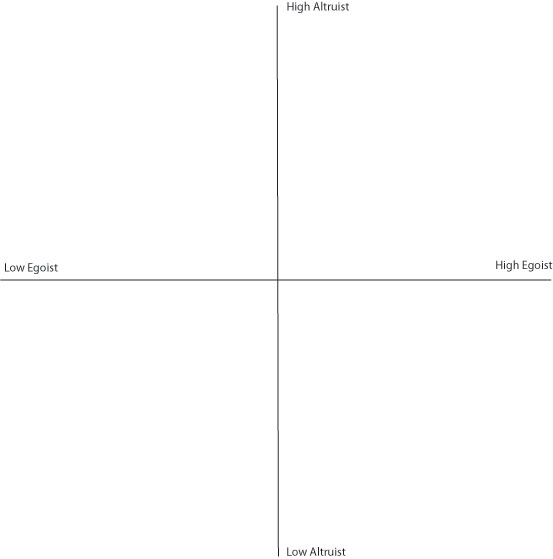

This method of 'measuring' altruism has obvious limitations and I was please to find, upon further reading, more developed ideas regarding the altruist/egoist continuum. The second method I came across used two axes, one to measure the degree of egoism and the other to measure the degree of altruism. This method acknowledges the fact that one's actions may demonstrate a high level of altruism, even though one also satisfies one's self through those same actions.

The third and most comprehensive I came across was to use this second method, but to apply it twice; once to intent and a second time to the outcome. So one's intent may be entirely altruistic, but the resulting action may in fact bring about personal benefits. This brought me to a place of personal rest, in that I had really struggled with the idea of ‘enjoying’ doing things for other people. I had become self-conscious about my own motivation for helping others.